Wilkes University Interim President Paul S. Adams announced on the evening of Sept. 12 the passing of Dr. Francis J. Michelini, who served as the second President of Wilkes College from 1970 to 1975. Click here to view his full obituary.

Michelini was the first Wilkes president to ascend from the academic ranks. He joined Wilkes in 1955 as the third full-time faculty member in the biology department. In 1963, he became dean of academic affairs, where he would leave his mark in the development of programs and majors.

After becoming president, Michelini – known to many as “Dr. Mike” – helped to ensure the University’s survival after the devastating flood caused by Hurricane Agnes in 1972. Using a boat owned by the University, Dr. Mike pitched in and rescued Wilkes-Barre residents stranded by the flood. The driving force behind what was known as ‘Operation Snapback,’ Dr. Mike brought together the campus community to assist in recovery efforts and ensure that campus was ready for classes in the fall of 1972.

On Nov., 10, 2015, Wilkes celebrated Michelini’s legacy by dedicating the residence hall at 80 West River Street in his honor. During this ceremony, the AFROTC Honor Guard presented the colors in recognition of Michelini’s service to his country in World War II.

Michelini was a frequent visitor to campus and regularly attended events, often traveling from his home in Mechanicsburg, Pa. in his bright red sports car.

In honoring Michelini’s legacy, News@Wilkes takes a look back to his service to the Wilkes-Barre Area during the devastation of Hurricane Agnes with the spring 2012 cover story of Wilkes Magazine, “Weathering the Storm.”

No one who experienced 1972’s Tropical Storm Agnes likely will ever forget it. Described then as the nation’s worst natural disaster, more than a hundred people were killed and at least 387,000 people were evacuated. Property damage was estimated at more than $3 billion—$16.3 billion in today’s dollars.

By far, the worst damage occurred in Pennsylvania, with more than $2 billion in losses occurring in the Susquehanna River basin. Wilkes-Barre was the hardest-hit community in the state. While the June 1972 event was devastating—and its aftermath a monumental challenge—those who experienced it witnessed a triumph of human spirit.

Dealing with the crisis “was a situation where you just rose to the occasion,” recalls Francis J. Michelini, then president of Wilkes College. “You did a lot of things instinctively. There was no preparation for such a crisis.”

Now a resident of Mechanicsburg, Pa., Michelini, 87, has vivid recollections of those high-water days. He was able to assist with dramatic rescues and help firefighters and utility workers by piloting through floodwaters in a 60-horsepower motorboat Wilkes owned for its environmental sciences program. Students on campus for the summer session first were evacuated to the nearby Hotel Sterling because of power failures. “I was a resident advisor, and our group went there with Dean (Jane) Lampe because the hotel had generators,” says Hedy Wrightson Rittenmeyer ’72, of Plano, Texas.

The normally scenic Susquehanna River, however, was threatening; and the Wilkes evacuees soon had to be rescued from the River Street location. Rittenmeyer remembers being plucked from atop the marquee of the hotel along with several other students.

At 6:15 a.m. on Saturday, June 24, 1972, the river crested in Wilkes-Barre at 40.9 feet, about 5 feet higher than protection levels. According to the National Weather Service, Agnes “rewrote the book on inland flooding and the impact a tropical storm can have hundreds of miles from the coast.”

Wilkes College faced an ordeal like none other in its 25 years as an independent, four-year institution. It suffered flood damage to all but one of its 59 campus buildings, and losses totaled more than $10 million. Severely impacted were the library, where 53,000 volumes were destroyed; Stark Hall, which sustained $500,000 in damages to delicate scientific equipment and tools; and the Dorothy Dickson Darte Music Hall, where at least $100,000 in musical instruments were lost.

“Do you stay in business? Or close up shop?” Michelini says he and other officials privately weighed the alternatives. They concluded that none of the buildings had damage to upper floors. They believed that academic programs were shaped by dedicated faculty and exchanges with students in the classroom—not by muddy bricks and mortar.

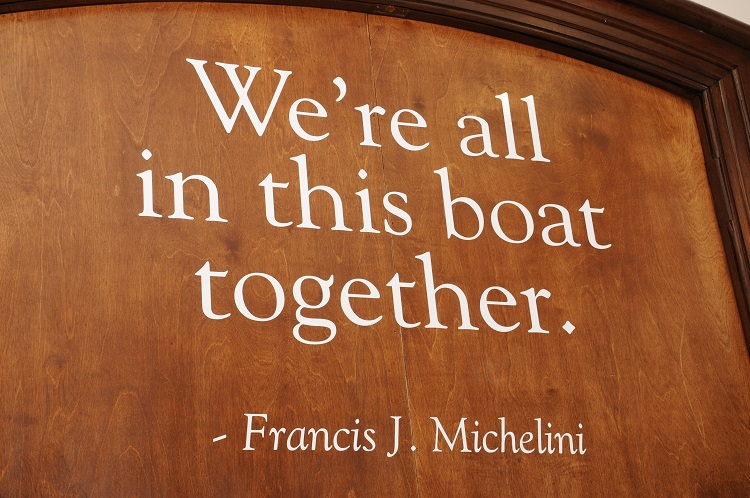

“We had the sense that we’re all in this boat together. Let’s get back on our feet and keep going,” Michelini says. An all-out recovery effort, dubbed Operation Snapback, was launched. The local newspaper reported: “Students and college personnel . . . responded to a plea for ‘manpower and elbow grease’ from the college president in an effort to overcome what had at first appeared to be an almost fatal blow.”

“It was devastating to see what had happened to the campus,” recalls Benjamin F. Fiester ’55, an emeritus professor of English who still teaches part-time at Wilkes. “But we were not all that depressed or unhopeful that we could (recover), and we did.”

Some of it was common sense, Michelini says. “You had to get the basics restored, like electricity. Then you had to get the mud out. The banks in town were underwater. We had salvaged a $25,000 fundraising check we’d received, and I remember telling someone to take it up to Hazleton to cash and use some of it to buy as many hoses and brooms and cleaning supplies as you could find!”

Summer classes reconvened within a week. Students helped with mud cleanup during the day and attended classes beginning at 3 or 4 in the afternoon.

Diana Gregory Finstad ’73, of Prospect Heights, Ill., did her share of scrubbing. “Those who worked tirelessly during the cleanup months truly understand the challenges and heartbreak faced during that time,” she says. “The flood of Agnes is a distant memory that I won’t forget. It ravaged the campus and left its mark, but it didn’t destroy the Wilkes spirit or my spirit.” (See sidebar for Finstad’s tale of her first trip to the Amnicola office after the flood.)

Michelini wrote many letters to prospective freshmen assuring them that classes would be held in the fall. Indeed, that semester began just one or two weeks later than originally planned, he recalls.

The college received about $12 million in federal disaster aid, and restoration efforts continued at a busy pace into October, November and December of that year. By the time spring semester ended, campus life was approaching normal. “We had a first-year anniversary party and told everyone to wear their flood clothes,” Michelini says.

Looking back, the former president credits the institutional culture at Wilkes for the successful recovery. As a small, cohesive community, communication throughout the campus and the administrative unit was effective.

“You only had to say something was needed, and it would get done. There was a hard-core group of wonderful people— many of whom had attended Wilkes themselves and came back to teach there. They did the job that was necessary to make sure we survived. No one person could do everything.”

Mass of Christian Burial will be celebrated 12 noon on Tuesday, Sept. 17, 2019 at St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church, 310 Hertzler Road, Mechanicsburg, Pa. Viewing will be held from 9:30 a.m. to 12 noon Tuesday at the church. Burial with military honors will take place at Gate of Heaven Cemetery, Mechanicsburg, Pa. For more information, please click here. A memorial service on the Wilkes campus is also being planned with details forthcoming.